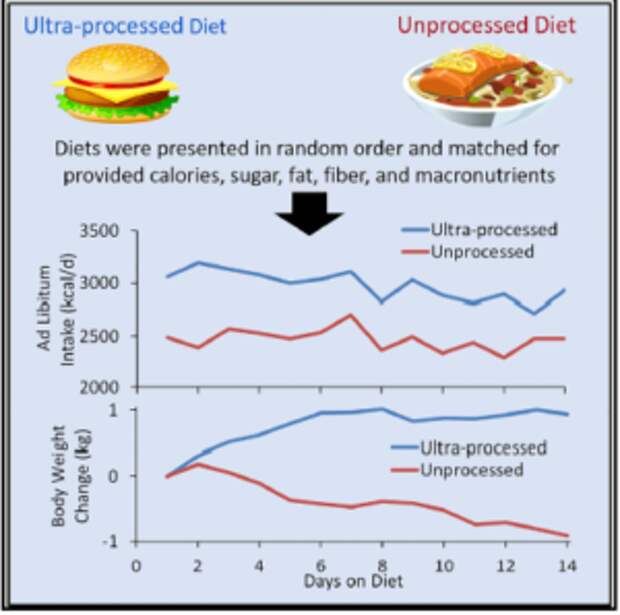

In considering the effects of ultra-processed foods, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) only dealt with observational research.

It excluded what I consider the most important study ever done to explain weight gain: the controlled clinical trial of ultra-processed versus processed diets done at NIH in 2019.

This study is hugely important for four reasons:

- The ultra-processed and minimally processed diets were matched for nutrients and palatability; study subjects could not tell which was which.

- Study subjects were in a metabolic ward, imprisoned; they could not lie or cheat about what they ate.

- The investigators were trying to disprove the idea that ultra-processed foods do anything special.

- The results were unambiguous; subjects ate 500 calories more on the ultra-processed diets; this is an enormous difference; studies rarely show anything like this.

The DGAC was instructed to ignore this study because it only lasted 4 weeks. This is a travesty.

But it is not the only travesty.

NIH has chosen to cut the capacity of the metabolic facility. It has reduced the number of beds to seven, shared among investigators, and allowing Hall only two beds at a time. This means any study with enough subjects to meaningfully answer questions has to be done two at a time, taking many months or years.

As a Senate Committee said in a recent report: NIH In the 21st Century: Ensuring Transparency and American Biomedical Leadership,

Writing in Politico a year or so ago, Helena Bottemiller Evich said:

Take NIH. In 2018, the agency invested $1.8 billion in nutrition research, or just under 5 percent of its total budget.

USDA’s Agricultural Research Service spends significantly less; last year, the agency devoted $88 million, or a little more than 7 percent of its overall budget, to human nutrition, virtually the same level as in 1983 when adjusted for inflation. That means USDA last year spent roughly 13 times more studying how to make agriculture more productive than it did trying to improve Americans’ health or answer questions about what we should be eating.Nutrition science has become such a low priority at NIH that the agency earlier this year proposed closing the only facility on its campus for highly controlled nutrition studies.

What’s going on? Why aren’t NIH and USDA doing everything possible to help prevent obesity and its consequences. Chronic diseases are leading causes of death and disability. Three quarters of American adults are overweight. The American public needs help.

Shouldn’t research on chronic disease be a major national priority?

Shouldn’t NIH be doing everything possible to answer questions about ultra-processed foods?

Kevin Hall explained the need in Science in 2020:

investment in research facilities for domiciled feeding studies could provide the infrastructure and staff required to simultaneously house and feed dozens of subjects comfortably and safely. One possibility would be to create centralized domiciled feeding facilities that could enable teams of researchers from around the world to recruit a wide range of subjects and efficiently conduct rigorous human nutrition studies that currently can only be performed on a much smaller scale in a handful of existing facilities.

I think yes.

The DGAC report called for research that

Tests the effects of dietary patterns with UPF that are matched for energy-density but vary in diet quality in relation to health outcomes, preferably using well-controlled trials in the U.S.

If the DGAC needs that research, NIH should insist on and enthusiastically support such studies.

The post Dietary guidelines II. Where is rigorous nutrition research? appeared first on Food Politics by Marion Nestle.